### 1. Control the Length of Critical Signal Traces

When designing high-speed circuits with fast edges, the transmission line effect on the PCB must be carefully managed. This is particularly important with the high-frequency integrated circuits (ICs) commonly used today, as they exacerbate the issue.

To minimize transmission line effects, there are several key guidelines to follow:

– For CMOS or TTL circuits with an operating frequency under 10 MHz, the trace length should not exceed 7 inches.

– If the operating frequency is around 50 MHz, keep the trace length under 1.5 inches.

– For frequencies above 75 MHz, traces should be no longer than 1 inch.

– For GaAs chips, the trace length should be kept to 0.3 inches or less.

Exceeding these lengths can result in signal degradation due to transmission line effects.

### 2. Plan the Cabling Topology

To mitigate the transmission line effects, it’s crucial to carefully plan the routing path and terminal topology. Cabling topology refers to the arrangement and sequence of network cables. High-speed logic devices with rapidly changing signal edges are highly susceptible to distortion caused by signal branch lengths, unless these branches are kept as short as possible.

There are two primary topologies commonly used in PCB routing: **Daisy Chain** and **Star Distribution**.

– **Daisy Chain Topology**: In this configuration, the wiring starts at the driver and proceeds sequentially to each receiver. If a series resistor is used to alter signal characteristics, it should be placed near the driver end. While Daisy Chain wiring can help control high harmonic interference, it is not always ideal for achieving optimal signal integrity. The key challenge here is minimizing the branch length. To ensure reliable signal transmission, the **Stub Delay** must be kept within safe limits, typically defined by the equation:

[

text{Stub Delay} leq text{Trt} times 0.1

]

where **Trt** is the response time of the signal. For example, in high-speed TTL circuits, the branch length should not exceed 1.5 inches. This topology is space-efficient and can be terminated using a single matching resistor, but it does not guarantee synchronous signal reception across all receivers.

– **Star Topology**: This topology resolves issues with clock signal synchronization, as each receiver is connected directly to the driver via a separate branch. However, manual routing on high-density PCBs can be difficult. Star cabling is typically done using automated routing tools. Each branch requires a terminal resistor that matches the characteristic impedance of the signal path. These resistance values can be calculated either manually or with CAD tools.

While simpler resistive matching is commonly used, more complex solutions such as **RC matching** terminals are available. RC matching can reduce power consumption and improve signal integrity, but it is typically used for stable, low-frequency signals, such as clock lines. The downside is that the capacitance in the RC circuit may distort signal shapes and slow propagation speed.

Another approach is using **series resistors**, which incur no extra power consumption but do introduce a small delay in signal transmission. This method is particularly useful for bus-driven circuits where time delays are not critical. Series resistors also help reduce component count and connection density.

For high-performance applications, the matching resistor is often placed near the receiver. This ensures that the signal is not pulled down and minimizes the risk of noise interference. This configuration is particularly common for TTL input signals (ACT, HCT, FAST).

Consideration must also be given to the type and installation of terminal resistors. **SMD (Surface Mount Devices)** generally offer lower inductance than through-hole components, making them preferable for high-speed applications. Among through-hole resistors, two mounting types are commonly used: **vertical** and **horizontal**. Vertical mounting has a shorter pin, improving heat dissipation, but may introduce more inductance if the installation is too long. Horizontal mounting reduces inductance but can lead to thermal issues, potentially causing resistance drift or failure.

### 3. Methods to Suppress Electromagnetic Interference (EMI)

Effective signal integrity solutions also improve a PCB’s **Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)**. One of the most effective strategies is ensuring proper grounding. A **signal layer** paired with a **ground plane** is an essential method, especially in complex designs. Additionally, reducing the outer signal density of the PCB can lower electromagnetic radiation. This can be achieved using **build-up** technology in PCB design, where thin insulating layers and microvias are used to create a compact layout. These layers help reduce overall PCB size and the associated current loop areas, thus decreasing EMI.

By reducing the PCB’s physical size, routing topology improves, with shorter branch lengths that directly result in reduced current loops. Since EMI radiation is proportional to the area of the current loop, smaller loops lead to better EMC performance. Additionally, high-density pin packages can be used, further shortening signal paths and enhancing the overall PCB’s electromagnetic performance.

### 4. Other Applicable Technologies

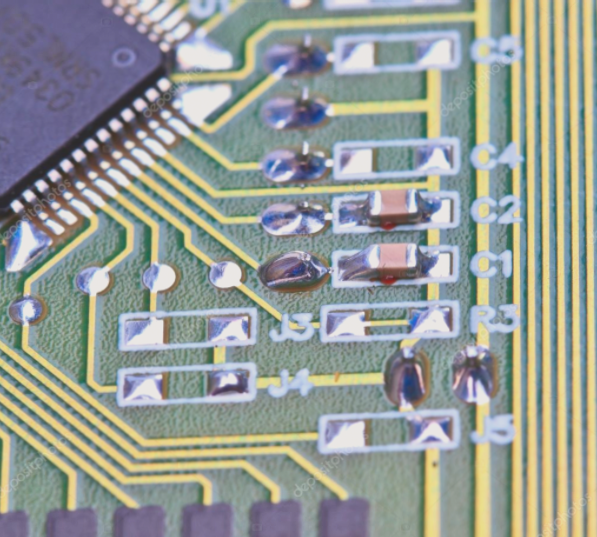

To reduce transient voltage overshoot on IC power supplies, **decoupling capacitors** are added close to the ICs. This technique smooths power supply fluctuations, minimizing the impact on the rest of the circuit and reducing power loop radiation.

Decoupling capacitors should be placed as close as possible to the power supply pins of ICs to maximize their effectiveness. For high-speed, high-power devices, grouping them together is recommended to minimize transient overshoot effects on the power supply. Without a dedicated power plane, long power traces can form loops that couple with signal loops, potentially generating EMI.

When it comes to cabling, loops are classified into **open loops** and **closed loops**. In open loops, the cabling does not form a complete circuit through the same network or cabling. In contrast, closed loops do form complete circuits and can become a source of **antenna effects**, radiating EMI externally and being susceptible to interference. The radiation produced by a closed loop is proportional to its area, making it a critical factor to manage in high-speed PCB design. Therefore, minimizing the area of closed loops and properly terminating them is essential for optimal EMC performance.